Introduction

In the previous article, I introduced the internal data structure of a postgres BTree index. Now it’s time to talk about searching and maintaining them.

I think that understanding this can help know when using a BTree makes sense and when it wouldn’t be very efficient.

Searching in a BTree

Initializing scankeys

In order to search in a BTree, postgres first uses the query scan to define scankeys. If possible, redundants keys in your query are eliminated to keep only the tightest bounds. If you did something real smart like

SELECT email, number_of teeth FROM crocodile

WHERE number_of_teeth > 4

AND number_of_teeth > 5

ORDER BY number_of_teeth ASC;

The tightest bound is number_of_teeth > 5, so the result of the query would be

email | number_of_teeth

----------------------------------------+-----------------

anne.chow222131@croco.com | 6

valentin.williams222154@croco.com | 6

pauline.lal222156@croco.com | 6

han.yadav232276@croco.com | 6

The BTree search function

The scankeys are passed to the _bt_search function.

Its purpose is to find the first leaf page where the scankey could be found.

In order to explain the _bt_search algorithm, I’m going to use the following query.

SELECT email FROM crocodile WHERE number_of_teeth >= 20;

Step 1: Initialize

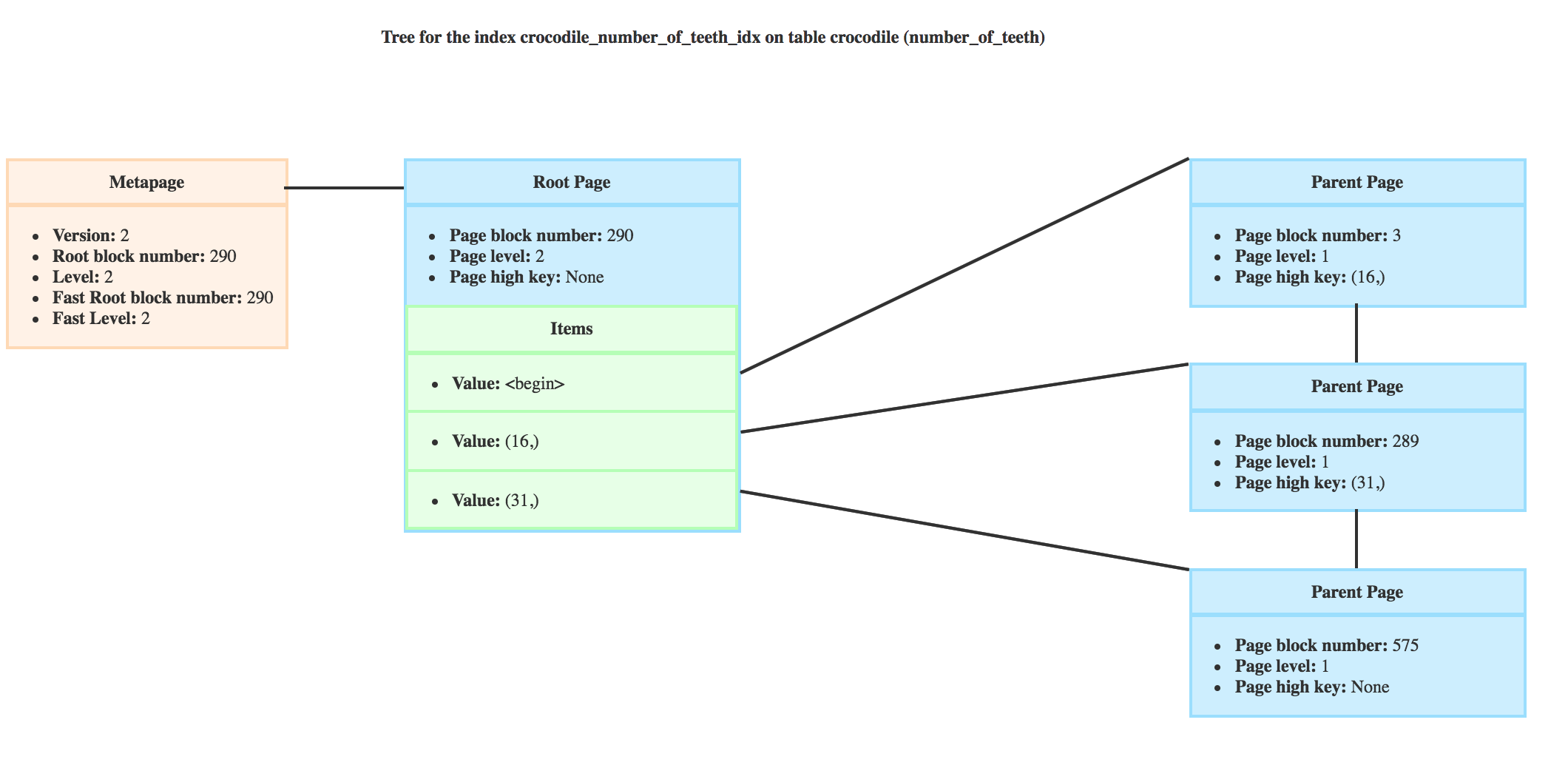

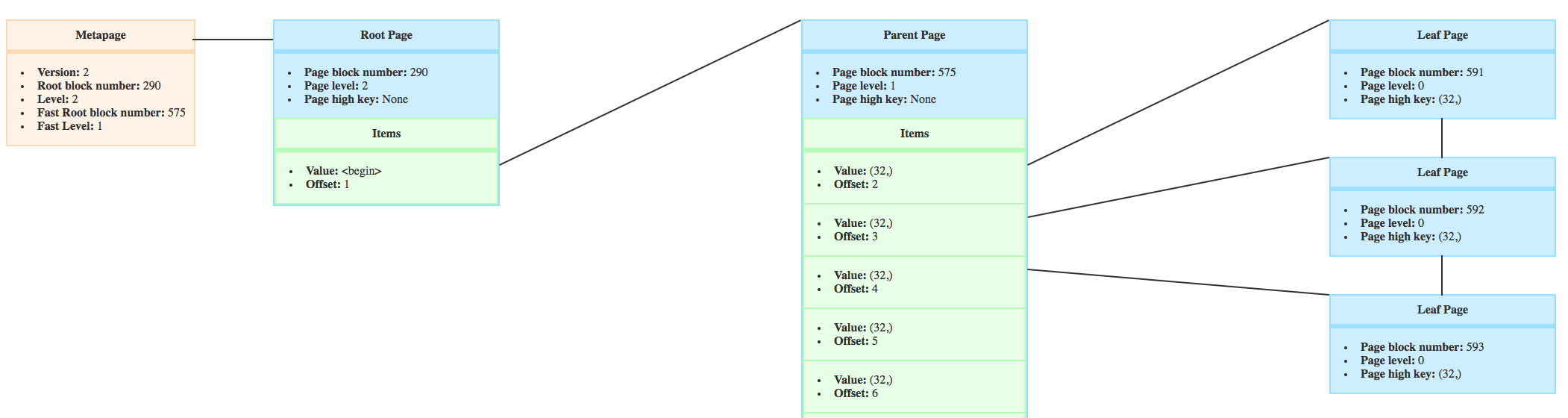

_bt_search initialize a page pointer bufP to the root or fast root.

At this step, if we take my BTree, bufP would be on the root with block number 290.

Step 2: Let’s climb down that tree

The second step is a loop iterating until the bufP pointer is a leaf page.

Step 2.1: should I stop looking ?

If the bufP page is a leaf page, we break the loop and return a stack containing:

- the block number of the parent page of the leaf

- the block number of the leaf page

- the offset of the first item in the leaf page matching our scankey

- the stack of the parent

This way we have the path leading to the leaf page.

Step 2.2: move right or not move right ?

At this point the function _bt_moveright is called.

It decides if it’s necessary to follow the right pointer of the current bufP page. This happens if, while descending on the tree, there was an insert.

It could then be possible that the current bufP page was split.

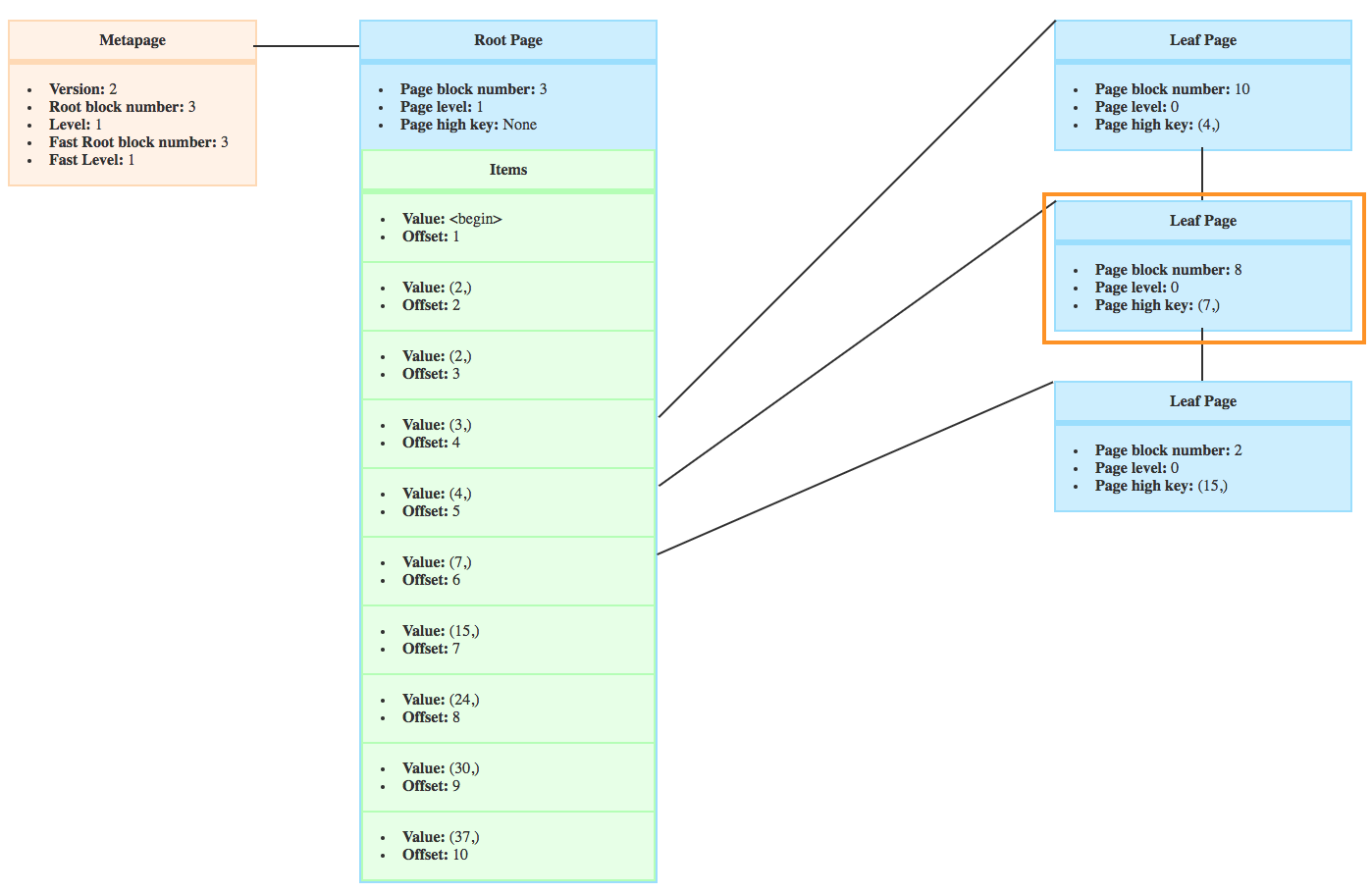

For example, the _bt_search for my previous query is looking for the first leaf page that could contain crocodiles with more than 20 teeth. The root doesn’t have a right page, so bufP wouldn’t change.

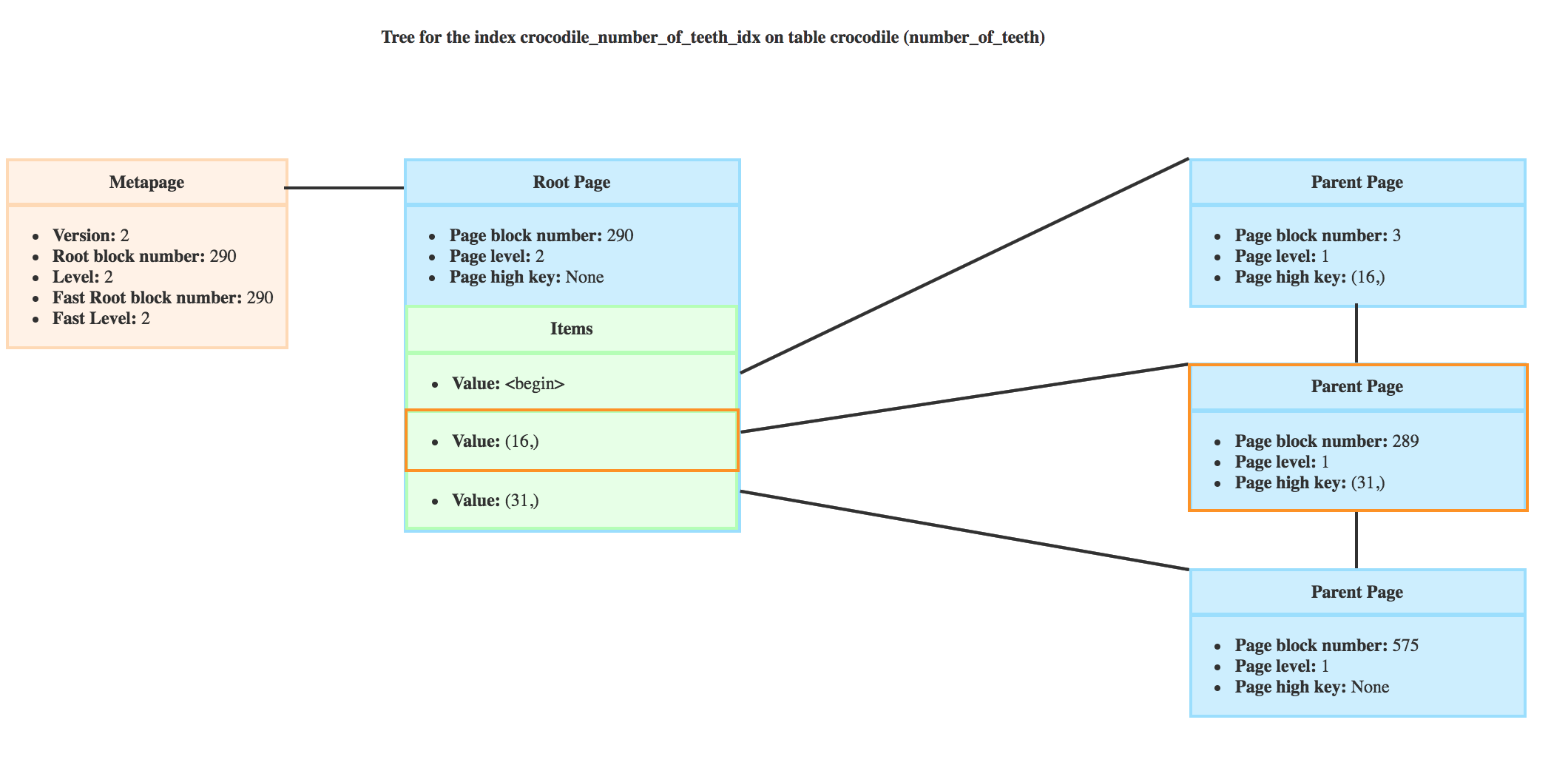

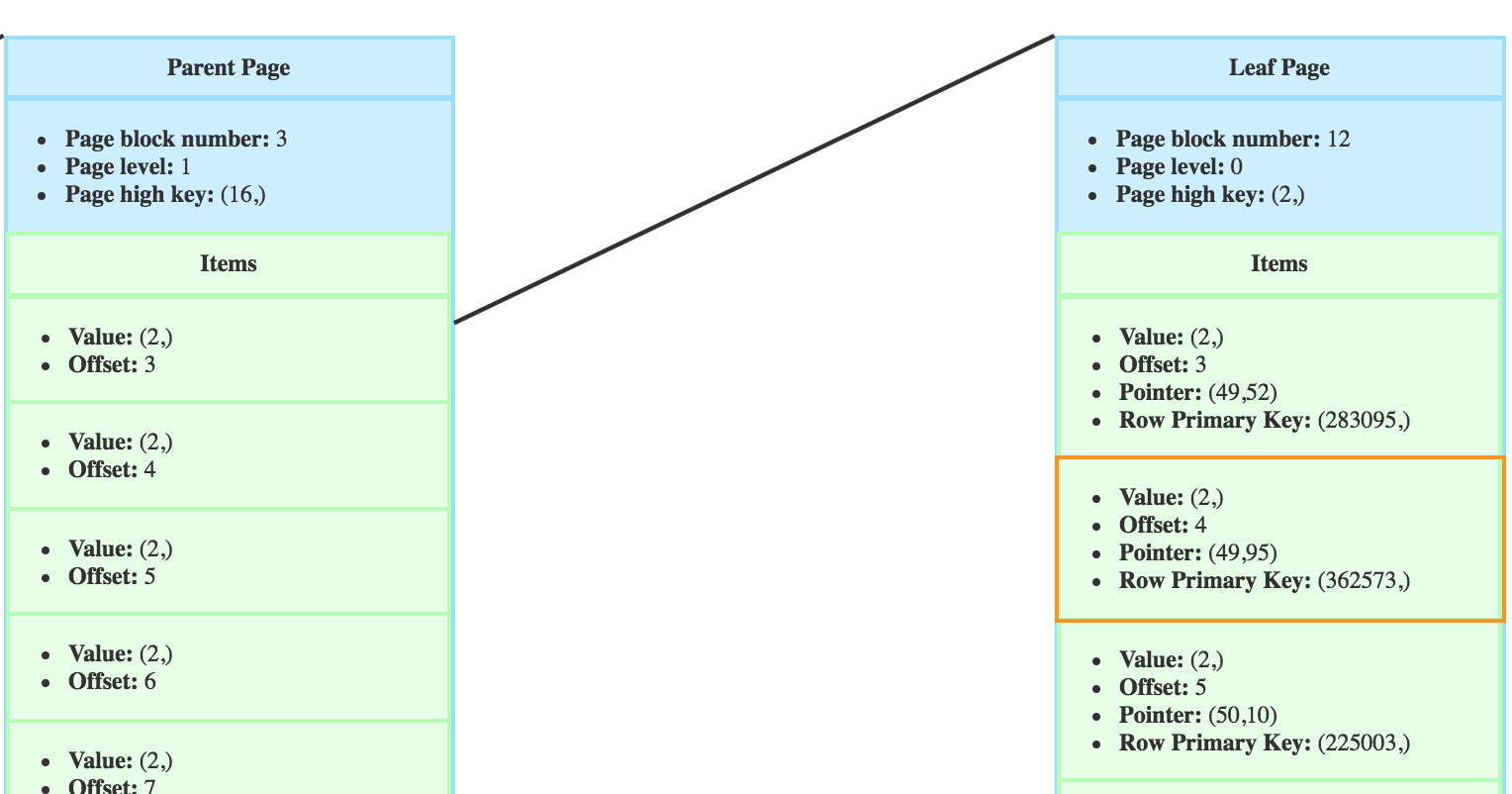

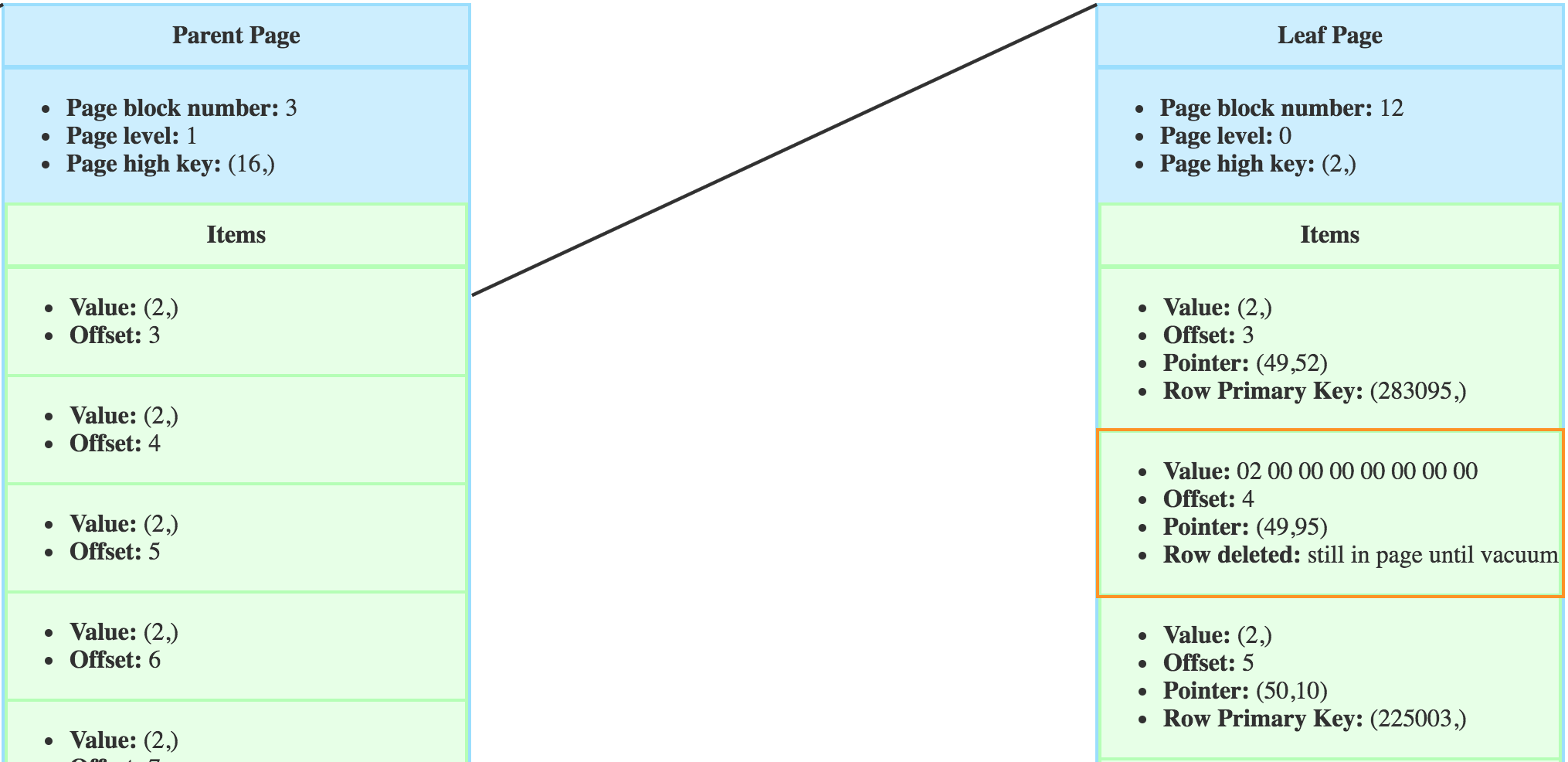

It would then descend on the page 289 where the high key is 31 and the minimum value is 16 like you can see here.

So the new bufP is the page circled in orange.

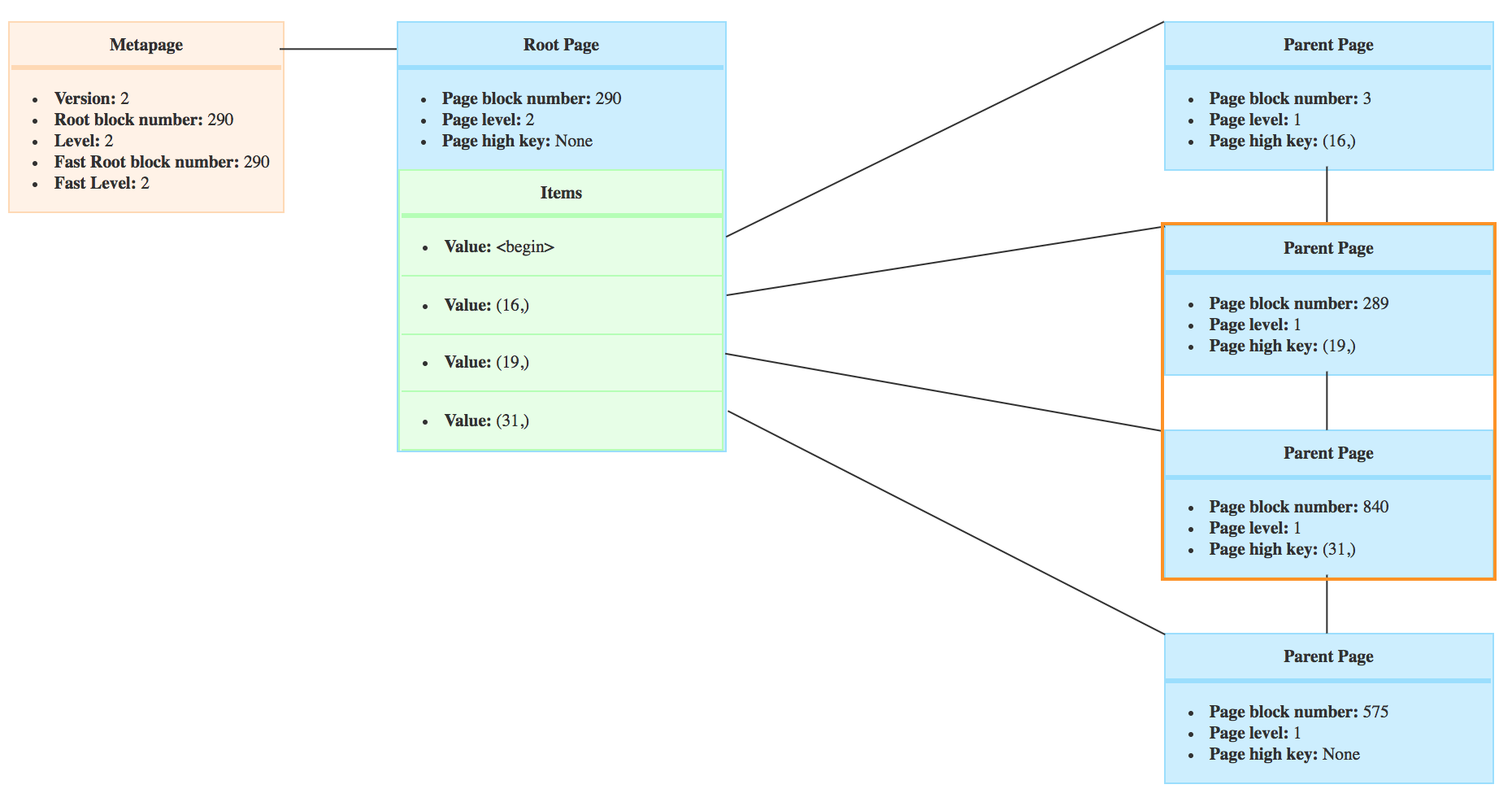

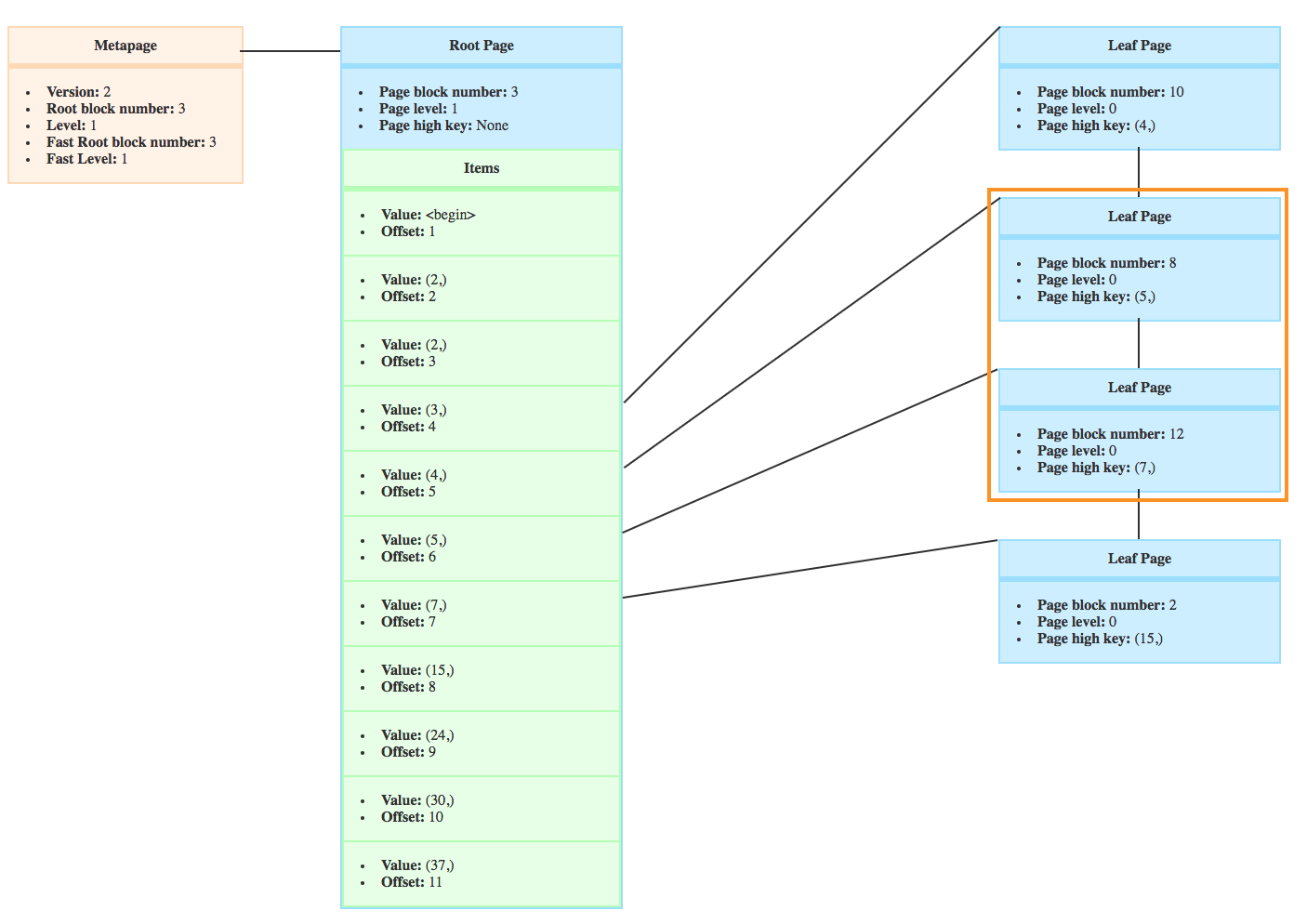

But let’s say, while the parents pages of the index were being explored, an insert forced the page to be split in two and the BTree looks like that

You can see that the high key of the page 289 went from 31 to 19 and the page has a new right sibling because it was split.

In this case, we know that the crocodiles with 20 teeth or more won’t be on the branch of the page 289 anymore, and the new bufPis set to the direct right sibling, so page with block number 840.

The algorithm moves right if the page high key is stricly lower than the scankey.

Step 2.3: looking into the bufP page items

Once the possibility of moving right has been explored, we now want to look into the page items to find the children page to follow.

At this point the function _bt_binsrch performs a binary search on the page’s items.

As I’m trying to actually make this article not too long (maybe you haven’t noticed ;) ) I won’t explain the binary search algorithm, but you can read the wikipedia article and the source code

If the page is not a leaf, it returns the offset of the last item with a value stricly lower than the scankey. So all the rows matching the clause can be found in the index after that item.

Let’s get back to our index and the query.

_bt_binsrch would return the offset of the item with value 16, as it’s not a leaf page and it’s the last item with a key lower than the scankey (which is 20)

In a leaf page however, _bt_binsrch returns the offset of the first element with a value higher or equal than the scankey.

Step 2.4: locking and moving

Once we have the offset of the item

- the block number of the page pointed by this item is retrieved

- the stack that will be returned at the end of the search is built

- the

bufPpointer is updated to point to the item child page - a read lock is aquired on the new

bufPpage and the read lock on the parent is released

About read locks

I mentionned the fact that we put read locks on the currently examined page. This read locks ensure that the records on that page are not motified while reading it. Of course, it doesn’t mean that there is not a concurrent insert on a child page, which is why we still need to possibly move to the right page.

To sum up

In a nutshell, the search algorithm is:

- Scankeys are created and if possible redundant keys are eliminated

- The current page is initialized to be the root

- While the current page is not a leaf page

- The high key of the current page is checked to decide if moving to the right is necessary

- If it is, the current page becomes the right page

- We use a binary search to find the last item with a value lower than the scankey

- The current page becomes the child page pointed by the item

Now let’s talk about inserts !

Inserting in a BTREE

Inserting into a BTree reuses a lot from the seach algorithm, so I will mainly focus on page splits.

In order to insert, scankeys are built.

Finding the right insert location

Then what we want is to find on which page our new tuple (key, pointer) should be inserted. Here there are two cases.

Index on an auto-incremented value

Very often an index is on an auto-incremented value, for example the primary key I used for the crocodile table is a serial, and of course postgreSQL created the crocodile_pkey on its own.

In this case a new key will always be inserted in the right-most leaf page. To avoid using the search algorithm to find the right page, postgres uses a fast path.

Step 1: retrieving the cached page The right-most leaf of the index is cached into a buffer. So we retrieve the page using this buffer.

Step 2: checking the page

There are three condictions that need to be verified in order to be able to use a fast path:

- The cached page must still be the right-most leaf page

- The first key on the page must be strictly lower than the scan key

- There must be enough free space on the page for the new tuple

If this conditions are met, the fastpath variable is set to true.

Index on a “normal” value

If the value of fastpath is false, it means that the indexes BTree has to be searched in order to find the right page for our tuple.

Step 1: searching for the right page

The insert uses _bt_search to find the first page containing the key. It’s the function called to search in a BTree, see above.

Step 2: locking

In the _bt_search we locked the page being red. Here we trade the read lock for a write lock.

Step 3: move right ?

It’s possible that, during the lock trade, the page was split. So as in the search algorithm, we re-use the _bt_moveright function to decide if it’s necessary to change the page to its right sibling.

Checking constraints

If we’re not allowing duplicates, postgres makes sure the key isn’t already in the index. Postgres can only detect that the value is not already in the index. So the write lock protects against concurrent writing on the page.

For example, I have a unique constraint on crocodiles email. Let’s say I run the query

INSERT INTO crocodile (first_name, last_name, birthday, number_of_teeth, email)

VALUES ('Louise', 'Grandjonc', '1991-12-21', 15, 'louise@croco.com');

The index has to be updated. A write lock is aquired on the index page where the tuple (louise@croco.com and the pointer to the new heap) will be inserted.

If there’s a concurrent writing, the second insert has to wait until the write lock is dropped. At this point the value louise@croco.com is already in the index.

So there is a conflict and the new tuple can’t be inserted and as the operations of insert and updating the index are atomic, the query fails.

Inserting the tuple and page splits

The function _bt_insertonpg() inserts a tuple on the page previously found.

1. Checking the tuple

The first thing that the function _bt_insertonpg() does is to check if the tuple can be inserted. It checks for example if the number of attributes in the tuple is appropriate.

2. Splitting the page if necessary

A page split occurs when there isn’t enough space to add the item in the target page, so a new page is created on the right of the page.

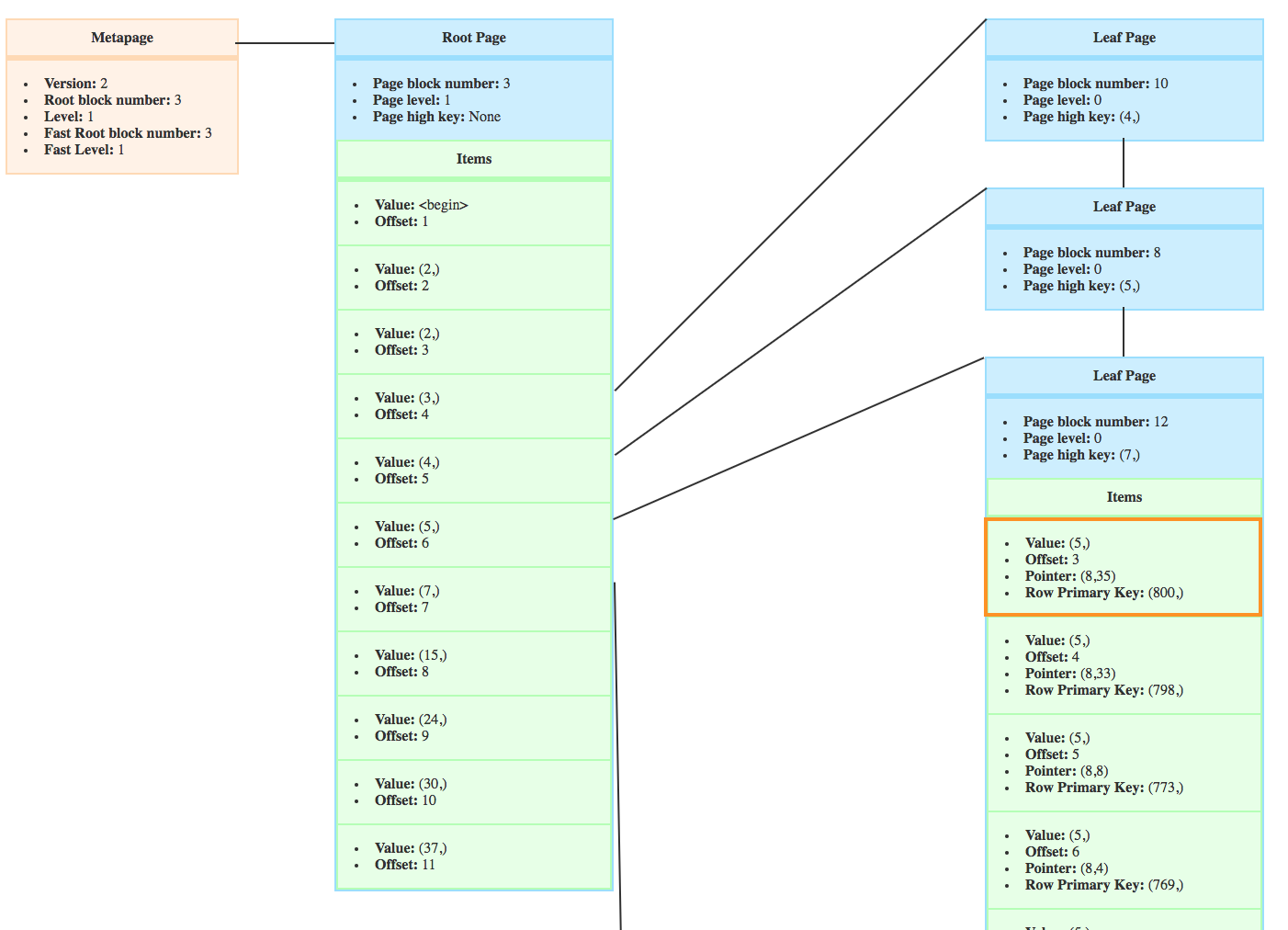

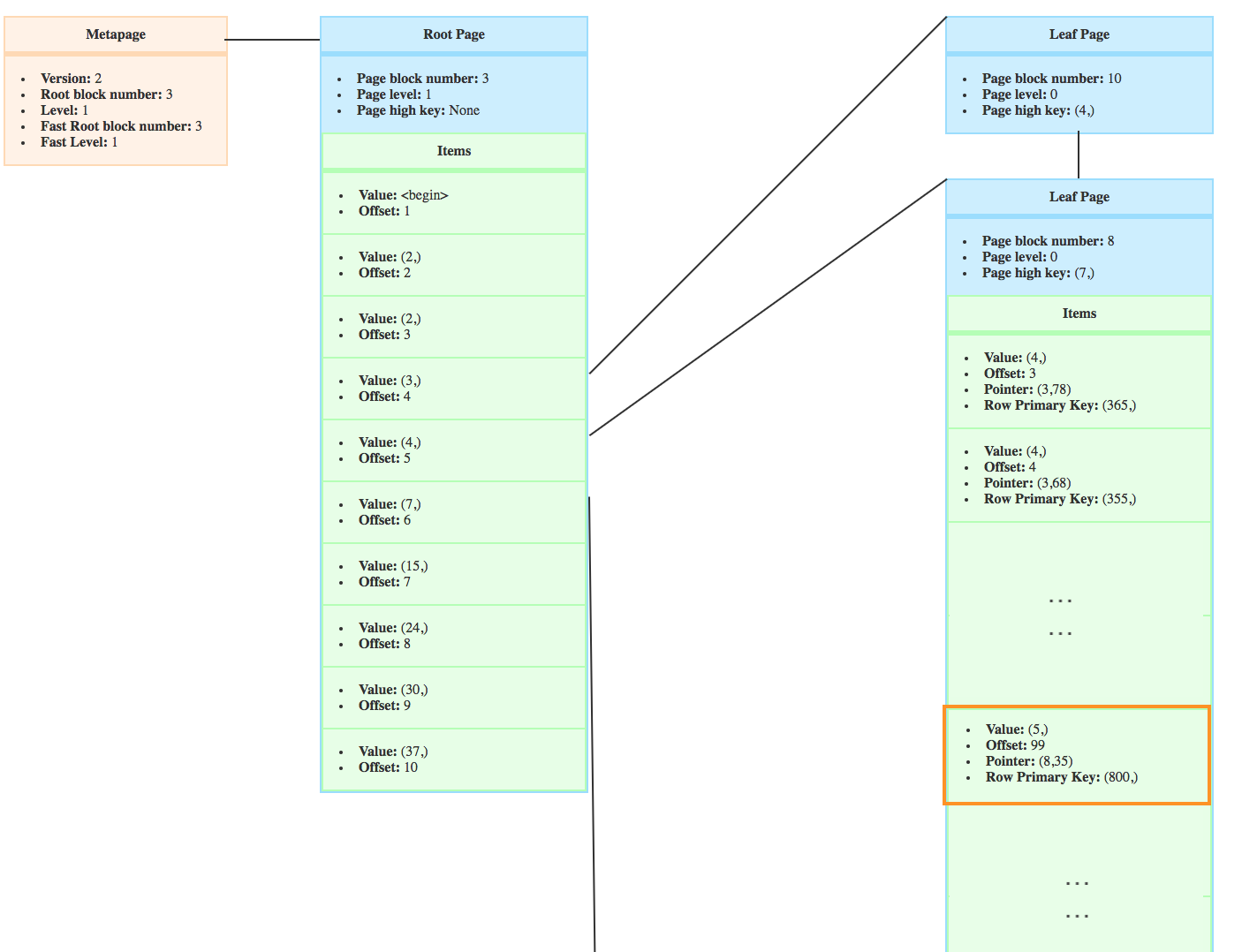

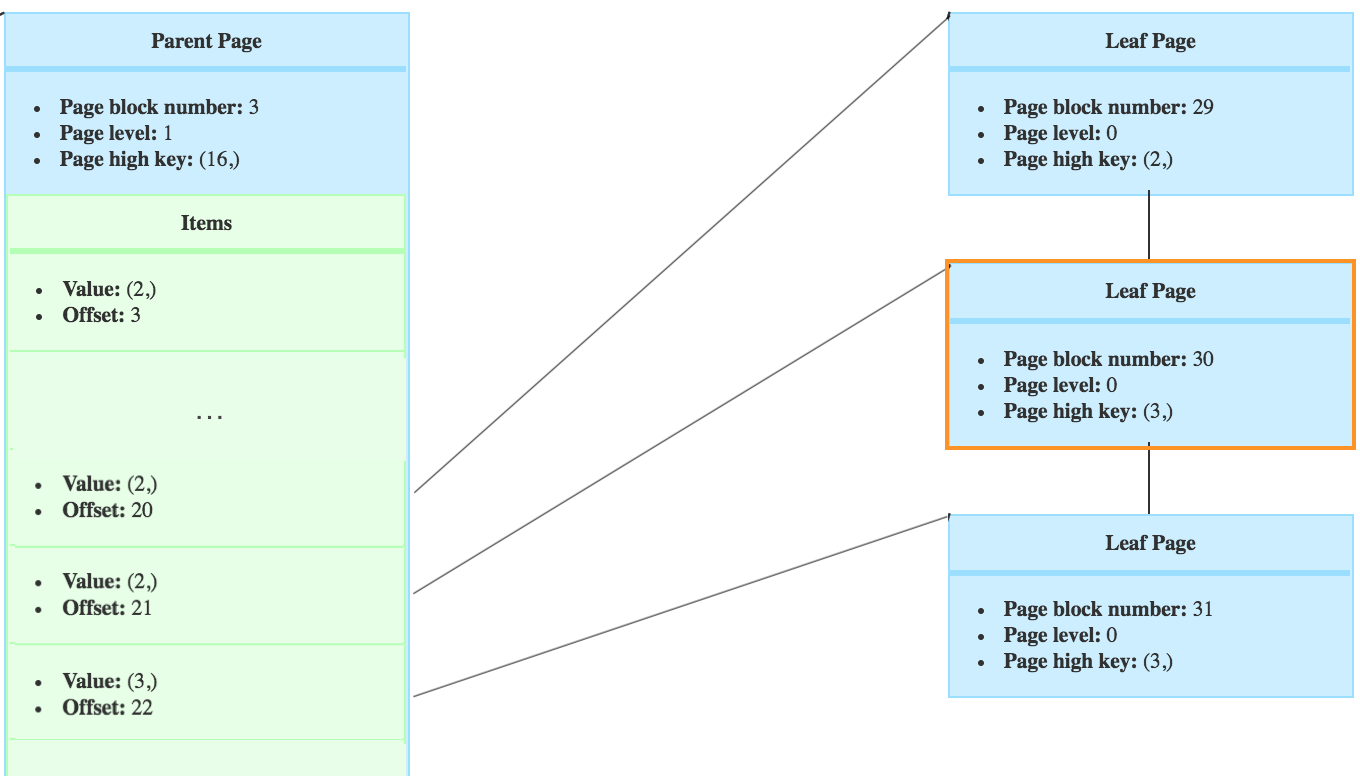

These screenshots are before and after inserts of crocodiles. (I re-created a new one which is why the root block number changed ;))

On the following screenshot, you can see that a new page appeared on the right and the high key changed. That’s because of the page split.

Step 1: is a split necessary?

In order to decide if the page should be split, _bt_insertonpg() compares the size of the item that we want to insert to the free space on the page.

If the free space is lower than the item’s size, then a split is necessary.

Step 2: finding the split point

You could think that it would be logical to simply create a new empty page and start filling it with the new tuples.

But let’s look more closely at the page split after the insert of crocodiles. Focus on the first item of the new page.

You can see here that it used to be in the target page.

Which means that, when postgres performs a page split, it does not simply create an empty page !

Postgres wants to equalize the free space on each page to limit page splits in future inserts. The goal being to limit as much as possible the number of pages in an index.

If it’s the right-most page on a level (so the last page of the level), instead of cutting in half, and having two pages with 50% of the data, the left page is filled as much as possible.

It’s useful for serial indexes, like the index on the id of my crocodile table crocodile_pkey. There is no reason to insert data on any other page than the right-most page as it’s a serial integer. So when a page split is necessary, if the left page only had 50% of the items, it would be forever half empty. Which makes no sense !

Step 3: splitting

So now that we have the split point.

A right page is created. In the right page, the data after the split point is copied. The data of the target page is updated to only keep the data before split point.

Then the pointers of the pages are updated. The right pointer of the target page becomes the new page. The right pointer of the new page is the old target page right pointer.

At last the high key of the pages are updated. The high key of the new page becomes the high key of the splitted target page. The high key of the target page becomes the first value of the right page.

3. Inserting on the parent level

If there was a page split, we need to insert the new page on the parent level.

If the split page was the root, there is no parent, in which case a new root has to be created with items linking to the target page and its new right page. The metapage is updated with the new root.

If it’s not a root, we need to insert in the parent page the tuple (value, pointer to new page). The value is the one from the first item of the new page.

Thanks to the stack leading to the target page, we know in which parent page the tuple has to inserted.

The function _bt_insertonpg() is called recursively with the parent page and the item.

To sum up

If I had to sum up the insert process, I’d say:

- The value to insert in checked to insure unique constraints do not fail

- Then we find the leaf page where the tuple (value, pointer) has to be inserted

- We try to insert it in that page

- If needed we split the target page

- If a split occured, a new item pointing to the new page has to be inserted in the parent level. This is where it’s recursive

- If needed the metapage is updated

Deleting from a BTree

Deleting items from a leaf page

When we delete a row from a table, the index has to be updated. Which means that any tuple in the leaf pages leading to this row has to be deleted.

The item is not immediatly removed from the index. It is first marked as deleted and will be ignored in index scans.

So if I deleted the row pointed by this item:

The item still appears until the next VACUUM.

The parents don’t need to be updated when deleting an item in a leaf page. The rest of the tree only changes in case of page deletion.

Deleting a page

A page is deleted only if all its items have been deleted.

When a leaf page is empty, it is marked with a btpo_flag as half-dead. So any concurrent search will ignore it and move right.

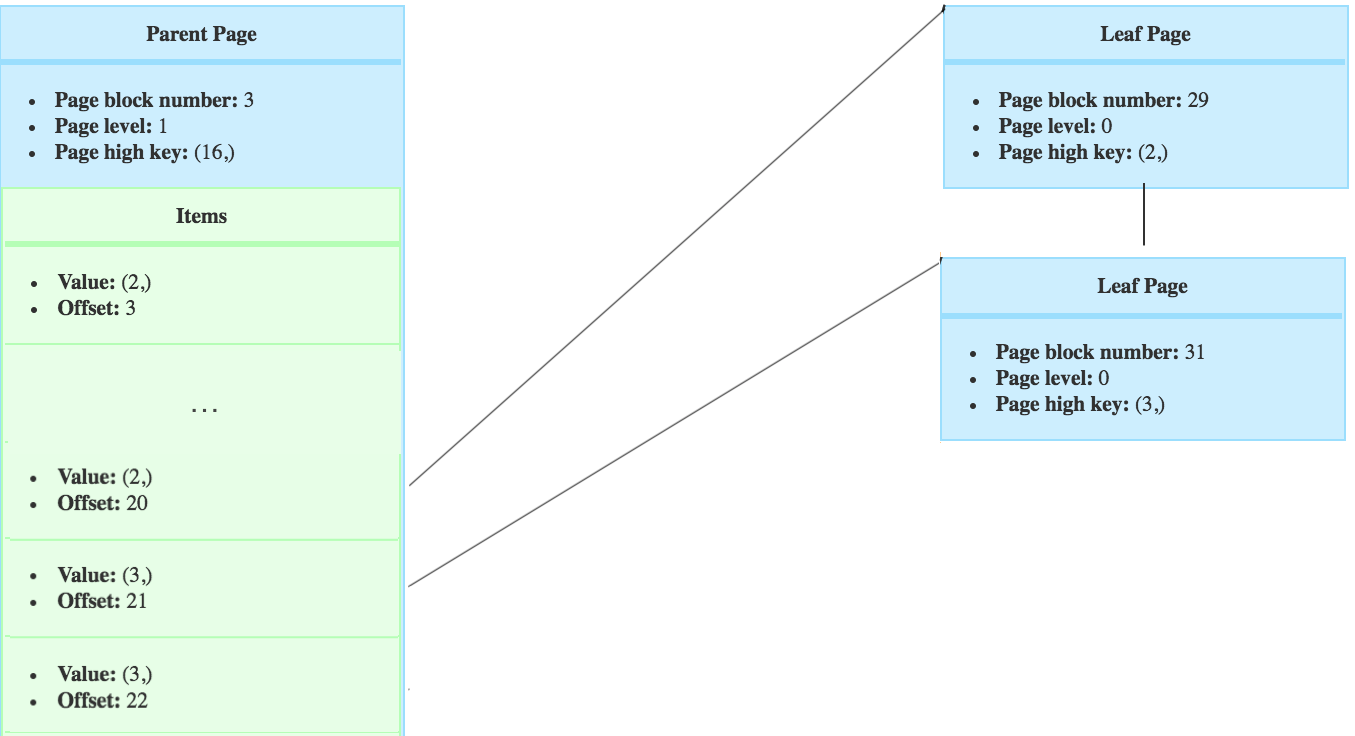

Then the page’s left page has to point to the page’s right page. If we deleted the page with block number 30.

Then the tree would look like this. The new right sibling from page no 29, is the page no 31.

The tuple that would have been inserted in page 30, will now be inserted in the right page.

Once the links have been updated, the page’s btpo_flags changes to deleted. The page is marked as deleted, but cannot be reused immediately because their could be other processes using it. For example a search can be in the parent page and has to aknowledge the fact that the page is marked dead.

A VACUUM will then reclaim the page under the condition that no processes is referencing it.. Once a page is free, it can be reused for a future page split and its content is overwritten.

The parent need to be updated to remove the downlink to the deleted page. If the leaf page was the last child of a parent page, then the parent page can be deleted. This process is recursive until the first grand-parent with more than one child.

About rightmost pages

The rightmost page of a level can never be deleted. This means that the height of a BTree can only grow.

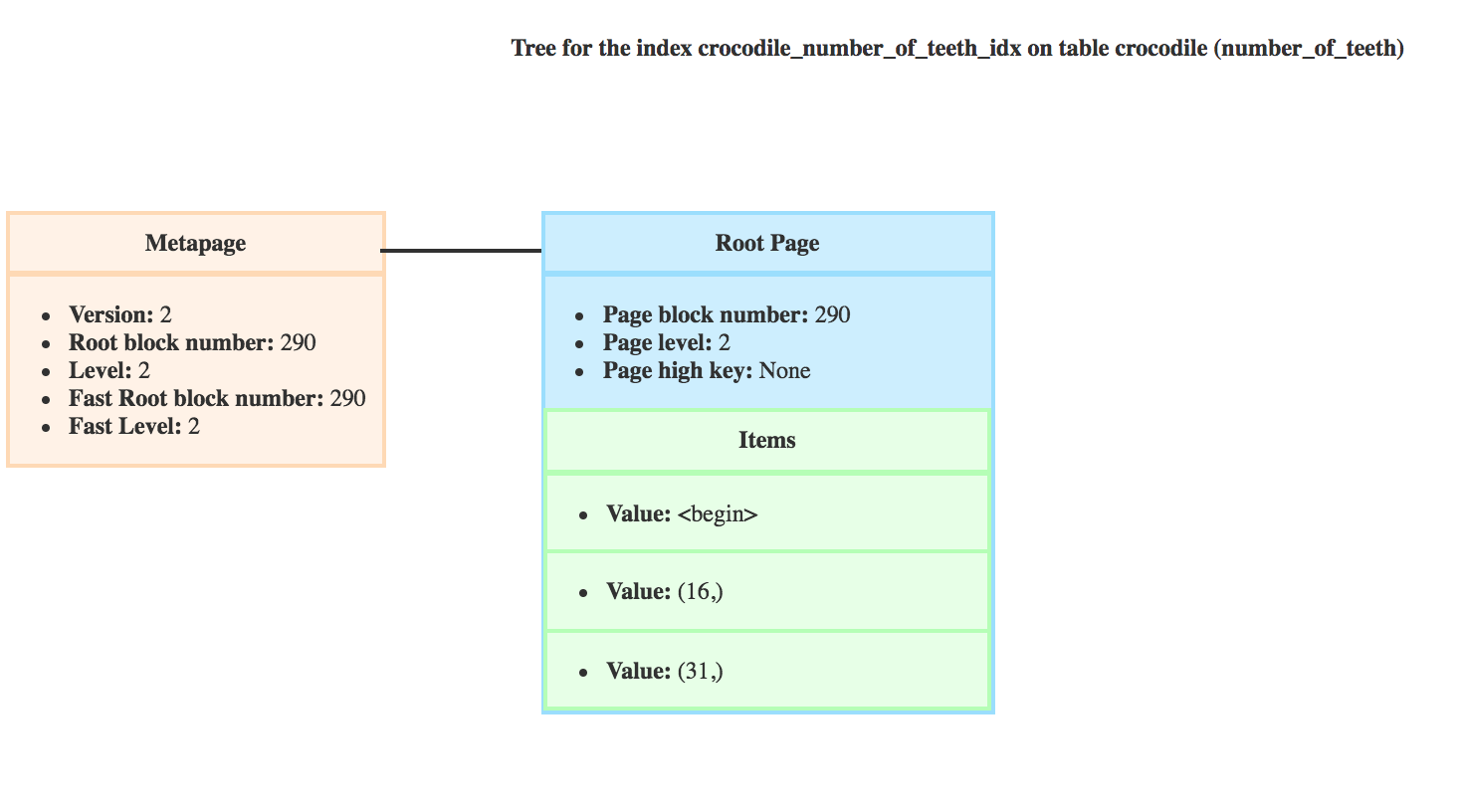

But if we delete a big amount of data, then it’s possible to end up with a tree with several levels with only one page.

On the following picture you can see that my root only has one child.

In this case, PostgreSQL updates the fast root of the metapage. The fast root becomes the first level with more than one child.

In this case, the fast root is the page with block number 575.

The fast root is used to optimize the search. Instead of starting from the root, it starts from the fast root, avoiding to climb down levels with only one child.

Conclusion

The entire structure of a BTree and the algorithms used to search and update are based on the idea that we are comparing a scankey with >, <, >=, <=, = operators.

This index is therefor efficient for this operations.

The next article will cover GIN indexes, as GIN indexes are based on BTrees, I hope that the article will be a little shorter…