Introduction

When I understand precisely what’s happening in my database, it helps me make smarter choices. It’s why previous articles focused on EXPLAIN and the algorithms used. Because to me, it was the best way to understand why things were not working as expected.

And I believe that when it comes to indexes, it’s the same. Of course you could use your ORM to add an index on a column you picked kind of randomly, but there’s a smarter way… First because ORMs create BTrees and if you’re using PostgreSQL there are other types that can be very handy. Understanding their structure, how they are searched and updated, might help you pick the one that best fits your usecase. I also hope that studying what’s going on internally might raise an awareness on the cost of having multiple (and some unused ;) ) indexes.

So in this series of articles, I will cover the magical world of the following index types:

- BTrees

- Gin Indexes

- GiST

- SPGiST

- BRIN

- Hash

Before I get into the subject, let’s understand what indexes are for. We talked a little bit about tunning queries, but that’s not their only purpose.

Let’s talk about crocodiles

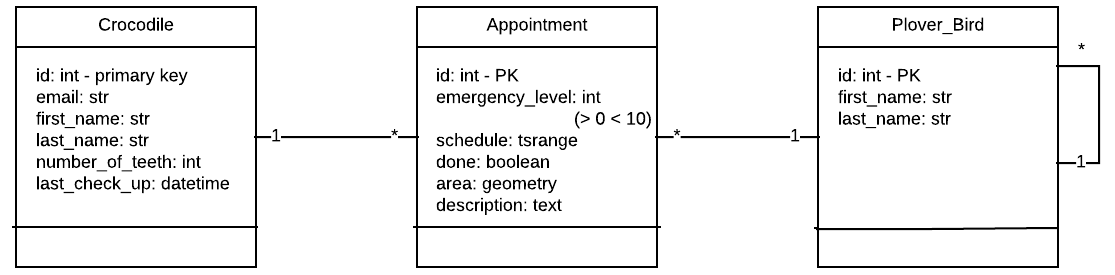

First of all, I’d like to introduce you to the data model I’m going to use for the examples.

Did you know that crocodiles love candies? Especially marshmallows ! So it’s very important for them to get their teeth cleaned, and the best at it are plover birds. If crocodiles don’t do it, they’re much slower at chewing things, and that’s a big problem!

So they have a website to get an appointment and give their current location (obviously it’s much easier for birds to fly to the crocodile than it is for crocodiles to walk to a bird). The goal is to find the closest free bird to intervene. Also birds have birds teachers. How would they learn how to clean teeth otherwise?

So here is the data model

And here is the SQL used to create the tables.

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS crocodile (

id serial,

email varchar(250) UNIQUE NOT NULL,

first_name varchar(250) NOT NULL,

last_name varchar(250) NOT NULL,

birthday date NOT NULL,

number_of_teeth integer NOT NULL,

last_check_up timestamp with time zone,

CONSTRAINT crocodile_pkey PRIMARY KEY (id),

);

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS plover_bird (

id serial,

first_name varchar(250) NOT NULL,

last_name varchar(250) NOT NULL,

teacher_id INTEGER REFERENCES plover_bird (id)

ON DELETE CASCADE DEFERRABLE INITIALLY DEFERRED,

CONSTRAINT plover_bird_pkey PRIMARY KEY (id)

);

CREATE EXTENSION btree_gist;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS appointment (

id serial,

crocodile_id INTEGER NOT NULL REFERENCES crocodile (id)

ON DELETE CASCADE DEFERRABLE INITIALLY DEFERRED,

plover_bird_id INTEGER REFERENCES plover_bird (id)

ON DELETE CASCADE DEFERRABLE INITIALLY DEFERRED,

emergency_level integer NOT NULL CHECK

(emergency_level > 0 AND emergency_level < 11),

schedule tstzrange NOT NULL,

done BOOLEAN DEFAULT FALSE,

area GEOMETRY(Point, 4326),

EXCLUDE USING GIST (crocodile_id WITH =, schedule WITH &&),

CONSTRAINT appointment_pkey PRIMARY KEY (id)

);

What are indexes for

Indexes have two purposes: constraints and query optimization.

Constraints

While working on your data model, you might notice that some constraints transform into indexes. There are three cases where an index is automatically created to insure the consistency of data when you add a constraint:

- PRIMARY KEY

- UNIQUE

- EXCLUDE USING

So for example, my crocodile table has the following indexes when I create it:

"crocodile_pkey" PRIMARY KEY, btree (id)

"crocodile_email_uq" UNIQUE CONSTRAINT, btree (email)

And same goes with the appointment table

Indexes:

"appointment_pkey" PRIMARY KEY, btree (id)

"appointment_crocodile_id_schedule_excl" EXCLUDE USING gist (crocodile_id WITH =, schedule WITH &&)

Postgres created these indexes for me and they’re ready to ensure consistency.

In my example I used a GiST index for the EXCLUDE. I’ll get back to it in the article on GiST. But what you can see is that the default index for constraint is a BTree.

And more generally, BTree is the default index when you use CREATE INDEX.

To sum up, indexes can be used as a data modeling strategy. If you have write latencies and trace it back to having too many indexes on a table, maybe these constraints indexes should not be the first to get rid of…

If you want to know more about constraints, I really recommend watching Will Leinweber’s talk on the subject. It also goes more into details of unique partial indexes.

Query optimization

The second use for indexes is to tune your queries. There’s a lot to think about when you decide to add an index. Maybe you are already using pg_stat_statements, if you don’t maybe consider it, it’s awesome :). So, often we want to add an index to make a particular query faster, and there a lot of questions appear:

- Which column(s) do I want to index ?

- What data type I want to index

- What operations are done on this columns (=, <, && etc.)

- Will this index usefull for other queries ?

- Do I really need an index ?

- …

All these questions are important.

The first three will help you choose an index type. By default PostgreSQL uses BTrees, maybe this is the one you need in your case, or maybe another type of index could fit better. If you’re a developer handling your indexes with an ORM, chances are that you won’t use them. Which is a shame.

As for the other questions, let’s remember that maintaining an index has a cost that varies depending on its type. Indeed, indexes are redundant, they repeat data from your table and have to be consistent with the data in the rows. Which means that when you change the actual data (on inserts, delete or update), the index will need to be updated.

For each index type, I will explain the algorithm used to maintain the data in the index, and I hope that it will help you understand why, for some indexes, there’s more risk to slow down your write queries.

Why do indexes make queries faster

In a previous talk I compared indexes in a database to the index of an encyclopaedia.

If you want to know everything about crocodiles, without an index you would need to read the entire encyclopaedia and read a lot of things you didn’t need. But instead, you go to the index and it gives you a list of pages to read.

A database index works the same. In the index, we store tuples with the value of the column(s) you want to index and a pointer to the row.

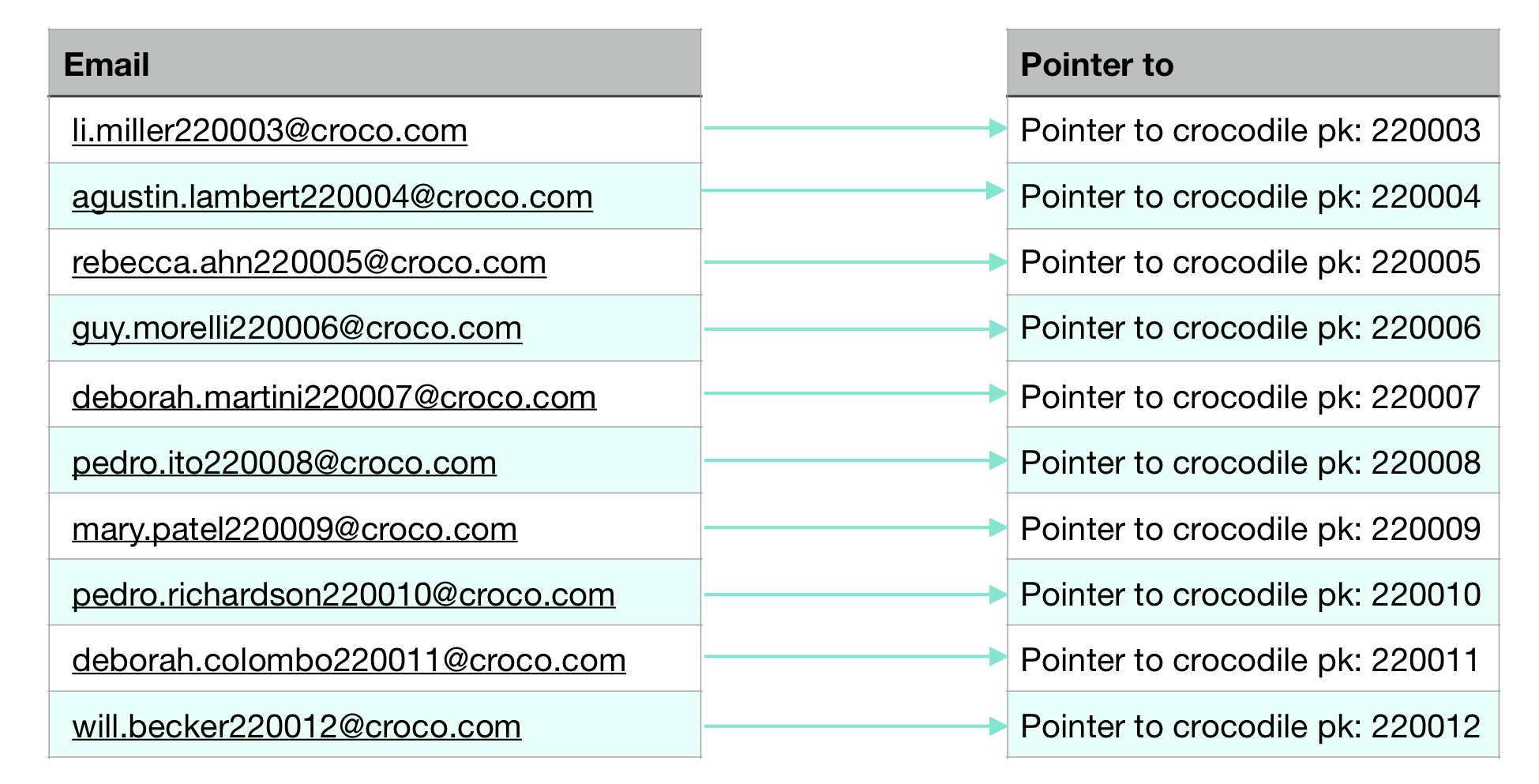

If we created an index for the crocodiles emails, it would look like that:

Here you can see tuples with emails and their respective pointers.

These tuples, are stored in pages.

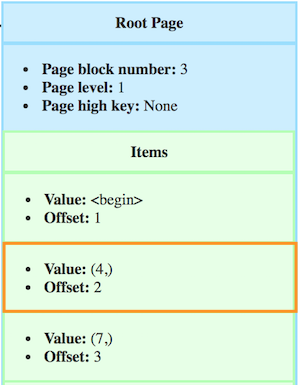

PostgreSQL uses pages to store data from indexes or tables. A page has a fixed size of 8kB. A page has a header and items. The items contain the actual data. So in an index, each item is a tuple (value, pointer).

Each item in a page is referenced to with a pointer called ctid.

The pointer consist of two numbers, the first being the number of the page (the block number), the second being the offset of the item.

If we took a page of an index:

The ctid of the item with value 4 would be (3, 2).

So, indexes and tables are arrays of pages.

For an index, having a simple list of pages would mean reading the entire index to get a value, so we instead use trees to optimize searching and updating. It’s the subject of the next article, understanding the BTree structure and how it’s implemented in postgres.

Conclusion

In this article, I didn’t want to go into too much detail about indexes types and strategies like multi-column or partial indexes. We will keep that for another day. The main thing to remember is that indexes have two purposes: contraints and optimization.

And now it’s time to take a little jump into the internal data structure of BTrees ! I know, this is very exciting…